Welcome back to The Assembly’s courts newsletter. We hope you had a relaxing, if scorching, July — and we especially wanted to thank those of you who took our survey. Your insights are shaping how we write this newsletter going forward.

Without further ado, let’s get to it.

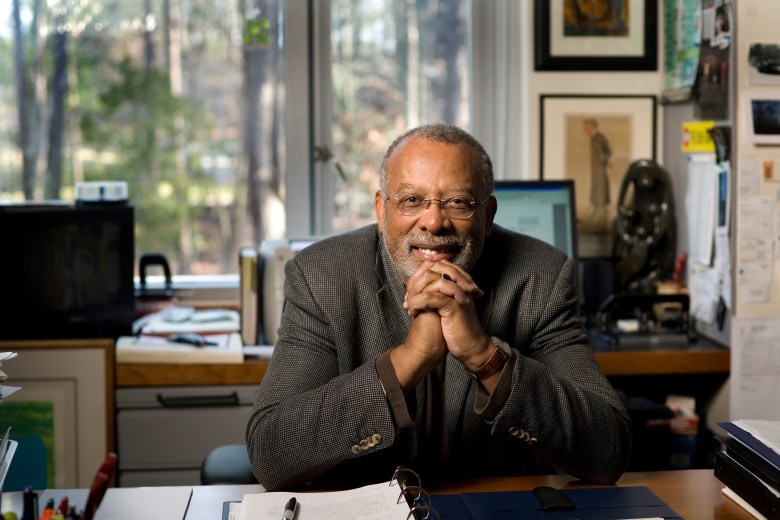

Duke Law Professor James Coleman believes the North Carolina State Bar’s dismissal of his complaint against the Forsyth County District Attorney’s Office points to a larger problem—a failure to hold prosecutors accountable for alleged misconduct.

Coleman, the director of the law school’s Wrongful Convictions Clinic, demanded in a July 19 letter that the state bar establish a task force to “review the integrity” of the bar’s complaint process and issue a public report. The bar has various ways to review complaints, including a Grievance Committee. Bar officials also can file complaints against attorneys, and attorneys found to have violated ethical rules can potentially lose their law license.

Prosecutors have fallen under increasing scrutiny for their role in wrongful convictions. The National Registry of Exonerations, a joint project of the University of California, Irvine, the University of Michigan Law School, and Michigan State University College of Law, has found that at least 54 percent of wrongful convictions are due to police or prosecutorial misconduct.

Coleman first filed a complaint with the state bar in 2014 against three Forsyth County prosecutors: Jim O’Neill, the current district attorney; David Hall, a former assistant district attorney who is now a superior court judge; and Tom Keith, who retired as district attorney in 2009.

Coleman alleged that the three prosecutors used a false affidavit from a former Winston-Salem police officer to undermine the innocence claims of his client, Kalvin Michael Smith. Coleman specifically accused Hall of helping produce the affidavit and said the former prosecutor should have known it was false because it contradicted what the officer wrote in her police reports.

Smith was convicted of robbing and brutally assaulting Jill Marker, an assistant store manager, in 1995. Smith has maintained his innocence, and a 2004 Winston-Salem Journal series pointed to numerous problems with the police investigation and prosecution—including allegations that a lead detective withheld favorable evidence and lied about Marker’s identification of Smith. Police never found any physical evidence that tied Smith to the crime scene.

The officer, Arnita Miles, said in an affidavit that Marker identified her attacker as a Black man immediately after her assault. But police reports at the time, including those from Miles, said Marker was incoherent and unable to identify anyone. Winston-Salem police spent six months pursuing a white man named Kenneth Lamoureux as a suspect before abruptly dropping him. (Lamoureux moved to Charlotte, was not charged, and died in 2011.)

The affidavit was never introduced as evidence in a court proceeding, but Coleman alleges that prosecutors still factored it into their case. O’Neill, he said, used the affidavit to accuse Smith’s supporters of falsely claiming Lamoureux as Marker’s likely attacker after a meeting he held in his office with Chris Swecker, a former FBI assistant director. Smith’s supporters had hired Swecker to investigate Smith’s case. Swecker subsequently released a report pointing out problems with the police investigation and calling for a new trial.

Coleman said Forsyth prosecutors weren’t supposed to be involved in Smith’s post-conviction appeals anyway because they had already declared a conflict of interest.

The state bar’s grievance committee dismissed Coleman’s complaint in 2015, saying it had found no evidence of misconduct. Coleman alleges that the bar failed to adequately investigate his complaint.

Katherine Jean, counsel for the bar, said she could not discuss a confidential complaint, but that the bar “regularly reviews its disciplinary processes to determine whether complaints are being handled consistently and objectively, regardless of a lawyer’s position or area of practice.”

“We are confident in the integrity of the grievance process and, in particular, that grievances against prosecutors are handled in the same manner as grievances against all other lawyers in this state,” Jean told The Assembly in an email.

Jean said the bar does not keep statistics showing how many prosecutors have been disciplined for alleged misconduct in the last five years. In several high-profile cases, the state bar has disciplined former Durham district attorneys Mike Nifong and Tracey Cline, as well as former Rockingham County DA Craig Blitzer.

Coleman said he is willing to take the matter to the N.C. Supreme Court.

Did someone forward this to you? Subscribe here to get our weekly courts newsletter.

On Our Radar

>> Stein v. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals

Attorney General Josh Stein has asked the U.S. Supreme Court to curtail journalists’ ability to make recordings on private property.

The case dates back to the 1990s, when two ABC News journalists famously went undercover as employees at a North Carolina Food Lion to report on unsafe food-handling practices. The store sued the network, alleging that its reporters had trespassed and breached their responsibility to Food Lion by recording unauthorized audio and video in nonpublic spaces.

The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in 1999 that the First Amendment did not shield the journalists from liability for trespassing and breaching their duty of loyalty (though it voided almost all of a multimillion-dollar verdict against ABC News). Two years later, however, the North Carolina Supreme Court said state law did not, in fact, cover employees’ duty of loyalty, only their “fiduciary duty.”

In 2015, the Republican-led General Assembly addressed this perceived oversight with the Property Protection Act, which enables businesses to sue employees who breach their “duty of loyalty” by disclosing private information or recordings made in nonpublic areas.

The state’s powerful agriculture industry backed it, as it would prevent animal rights groups from producing undercover videos. People for the Ethical Protection of Animals and other groups sued, and a federal judge ruled in 2020 that the law was unconstitutional. A split Fourth Circuit panel agreed—though it said the law was only unconstitutional for individuals involved in “newsgathering activities.”

Stein, a Democrat running for governor, asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the state’s appeal in late June. Drawing heavily from the dissent of Judge Allison Rushing, a Trump-appointed Fourth Circuit judge, Stein argued that the Fourth Circuit had reversed its own ruling in the Food Lion case. He also said the Supreme Court should take the case because other appeals courts had reached different conclusions on the same question. The Ninth Circuit, for example, ruled that all recordings are constitutionally protected, while it and the Tenth Circuit split over “duty of loyalty” laws.

In an amici brief, the American Farm Bureau Federation, National Pork Producers Council, and other Big Ag organizations inveighed against “the danger of an overly broad First Amendment right to gather information” that interferes with farmers’ “right to exclude from their land antagonists who seek to do them harm.”

A separate amici brief filed by the Republican attorneys general of Utah and 15 other states asks the Supreme Court to “resolve the confusion” over whether there is a constitutional right to record on private property. The First Amendment, the states argued, “does not require private property owners to permit people to enter their land for information gathering, whether those people are trespassers, spies, or bona fide journalists seeking information on a story.”

PETA’s response is due this week. It’s not clear when the Supreme Court will decide whether to grant the state’s petition.

>> Judge Ashley Watlington-Simms v. the First Amendment

North Carolina juvenile court records are sealed, but hearings are open to the public—until a judge declares them closed, which can happen for any or no reason. At the same time, state law allows journalists to report on what happens in an open court proceeding.

There’s no exception for juvenile hearings, for good reason. While the law aims to protect children ensnared in the justice or family court systems, the public still has a right to know how judges—who are, after all, elected officials—conduct themselves.

That fact seems to have been lost on District Court Judge Ashley Watlington-Simms. On July 28, Watlington-Simms learned that Greensboro News & Record reporter Kenwyn Caranna was in her Guilford County courtroom. According to the News & Record, Watlington-Simms refused Caranna’s request to consult with a lawyer, told her she was under a gag order, and instructed bailiffs to seize her notes.

Then, on August 2, Watlington-Simms issued a protective order sealing Caranna’s notes and forbidding her from disclosing what she witnessed. In the order, Watlington-Simms said that Caranna “can make a motion for the release of the notes seized and placed under seal by the Court,” the N&R reported.

According to state law, “No court shall make or issue any rule or order banning, prohibiting, or restricting the publication or broadcast of any report concerning … any evidence, testimony, argument, ruling, verdict, decision, judgment, or other matter occurring in open court in any hearing, trial, or other proceeding.”

That’s precisely what Watlington-Simms did. And in preemptively barring Caranna from discussing an open judicial proceeding, Watlington-Simms engaged in what is known as “prior restraint,” possibly violating a well-established First Amendment principle.

It’s not clear how Watlington-Simms justified her decision to seize Caranna’s notes—a district trial court coordinator refused to release the protective order to The Assembly on Monday, calling it confidential—but it, too, seems dubious. In 1999, the General Assembly passed a “shield law” that protects journalists from having to disclose “any confidential or non-confidential information, document, or item obtained or prepared while acting as a journalist.” (For example, a reporter’s notes.)

Journalists’ protection is “qualified,” which means reporters can be compelled to turn over documents if a judge determines that they are “relevant and material to the proper administration of the legal proceeding,” “cannot be obtained from alternate sources,” and are “essential” to the legal claims of the person seeking the documents.

Caranna’s notes don’t meet those three criteria. Even if they did, the law says she can’t be forced to turn them over before a hearing.

All of this seems to contradict Article 1 of the North Carolina Constitution: “Freedom of speech and of the press are two of the great bulwarks of liberty and therefore shall never be restrained, but every person shall be held responsible for their abuse.”

The N&R has requested a hearing to vacate the gag order, which likely won’t occur for several weeks. Stephanie Wallace, the trial court coordinator, told The Assembly that Watlington-Simms will be out of the office until August 21.

But state law suggests that the N&R’s compliance with Watlington-Simms’ edict is voluntary: “If any rule or order is made or issued by any court in violation of the provisions of this statute, it shall be null and void and of no effect, and no person shall be punished for contempt for the violation of any such void rule or order.”

Have any suggestions for improving this newsletter or stories we should look into? Email us at courts@theassemblync.com.

Is This Asheville Photographer a Wronged Artist or a ‘Copyright Troll’?

David Oppenheimer has filed more than 170 infringement suits. Experts say the law that’s made him a fortune needs reform.

An NBA Star’s Grief and an Ongoing Search for Justice

Chris Paul’s memoir talks about his grandfather’s murder. But evidence suggests the case against five teens wasn’t so straightforward.

A Man Alone

Craig Waleed’s time in solitary confinement almost broke him. Now he works to ensure others don’t suffer the same isolation.

The Assembly is a digital magazine covering power and place in North Carolina. Sent this by a friend? Subscribe to our newsletter here.